What US Tariffs Really Mean

Let’s start with the numbers. And the numbers are actually quite benign — in 2024, the US GDP was estimated at $29.2 trillion. Imports totaled $4.1 trillion, while exports reached $3.2 trillion.

This isn’t to say that trade doesn’t matter. But both the US and global economies have shifted heavily toward services since the last time US tariffs played a central role in economic policy back in the 1930s.

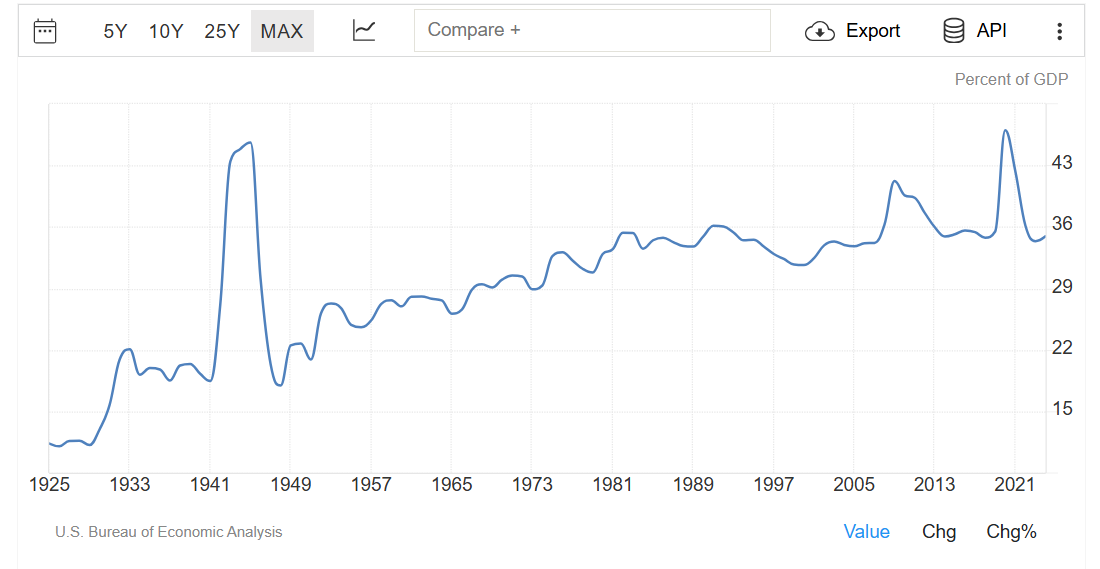

Moreover, the nature of the world’s economies has undergone significant changes. In 1929, US government spending was approximately 9% of the GDP, while in 2024, it was nearly 35% of the GDP. That dynamic is also true for most global economies today, certainly for all the G7 countries.

Government Spending Has Changed the Role of US Tariffs

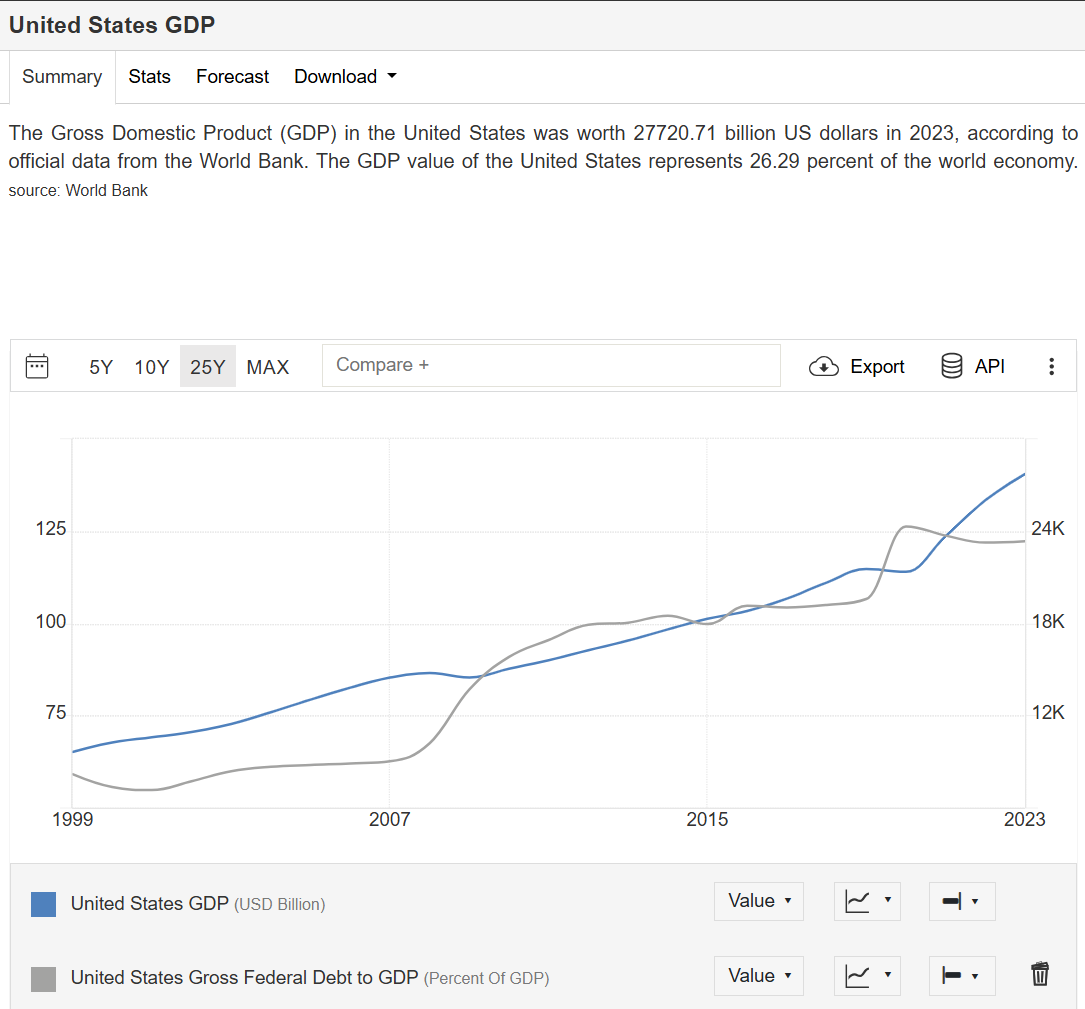

What has dramatically changed since 1929 is that government interventions and spending have largely balanced the business cycle. During turbulent times when the private sector is pulling back, governments and central banks have started to step in. During good times, intervention or support is supposed to be decreased. The only problem, especially since 2008, is that once governments start supporting the economy, the willingness to take that support back has been lagging. This is best seen in the Government Debt/GDP ratio, courtesy of Trading Economics.

The US GDP in 2008 was $ 14.8 trillion, which decreased to $ 14.5 trillion during the Great Financial Crisis. Clearly, the government was expected to step up, and it certainly did – the US government’s debt-to-GDP ratio went from 67.5% in 2008 to 82.5% in 2009. The problem is that it continued to grow – largely unchecked. Obviously, the current levels are high, with debt-to-GDP reaching 122% in 2024, prompting some credit rating agencies to downgrade the US government’s credit rating.

Pictured above: US Government Spending as % of GDP

Clearly, the US can not hope to get government debt under control if the government spends 35% of GDP annually, even in good times. The spike above 40% in 2020 is probably justifiable, given that the economy was on the brink. Still, over the last decades, the US has never had government spending below 33% of GDP when, in the 1980s and 1990s, would have been considered very high. It is one thing to have government spending at 33% of GDP when the debt-to-GDP ratio is 50% or even 60%; it is entirely different when the debt-to-GDP ratio is 122% and the budget deficit in 2024 was 8% of GDP.

How US Tariffs Act as Stealth Taxes

What is the most effective way to reduce government debt? The best course is DOGE – an agency tasked with reducing government expenditures. However, that may be a slow process and not enough. We have reached a level of indebtedness that makes raising taxes inevitable.

And what is the best way to raise taxes without explicitly stating that you are going to raise taxes? Answer: Beautiful Tariffs!

Allow us to explain. If there is a tariff on all Canadian imports, one of the goods most likely to be impacted will be Canadian wheat. If tariffs are introduced, American farmers will likely plant more wheat, and the economy will produce more wheat – thereby substituting for imports, potentially at a higher price.

What about European wines? Unfortunately, wineries take at least three years to yield a crop. Clearly, that would be a risk – what happens if tariffs are not there for 3 or even 5 years? However, even before that could happen, Americans would have to import wine for three full years, as domestic production is unlikely to increase next year.

The revenue from those tariffs will be deposited directly into the Treasury. What actually happens to US domestic wine production? It will likely increase, eventually, but probably not enough to replace imports, as there is limited visibility into what happens in the long run. Grapevines usually have a life expectancy of 25-30 years. It is premature to expect that US wine imports will be completely replaced by domestic production soon.

Therefore, that source of revenue will primarily function as a tax on wine, even though it is not labeled as such, potentially for an extended period. At least 3 years before domestic wine production can be significantly increased.

Environmental Limits: Aluminum and the Limits of Tariffs

Finally, we are going to aluminum smelters. Aluminum smelters are among the worst environmental polluters. According to Wikipedia, there are 15 aluminum smelters in the US and more than 75 in China. Those in China, in general, have capacities several times higher than those in the US.

There is a good reason for that – building new aluminum smelters is probably so difficult in the US due to environmental regulations, and in our opinion, no level of tariffs is going to change that.

Moreover, there is no indication that tariffs will remain at current levels beyond the Trump administration. Investors typically require at least 20 years, and sometimes even longer, to build new smelters.

Clearly, US domestic aluminum production is unlikely to increase significantly in the next several years, possibly even decades, and the tariffs are unlikely to change that. However, what will change is the government revenues from tariffs!

Conclusion: The Real Role of US Tariffs Today

There’s plenty of confusion surrounding the Trump administration’s use of US tariffs. But they aren’t irrational. In fact, tariffs may be one of the most effective tools for increasing federal revenue without formally raising taxes.

Could some industries return to the US from China or Mexico? Possibly. But that’s uncertain. What is certain is this: US tariffs will increase government revenue. Unfortunately, the US has reached extremely high levels of public indebtedness, and swift and effective measures are necessary.

It seems like the Trump administration is doing a good PR job selling the tariffs as a way to support the American economy. Tariffs can eventually be good for the American economy, but they will help reduce the US government deficit.

Whether you support or oppose them, US tariffs are now a central pillar in America’s economic strategy.